With the following button you will be redirected to Google Translate:

to Google TranslateItalia e UE – Italien und die EU

Un rapporto che il coronavirus ha reso anche più difficile - Eine Beziehung, die durch das Coronavirus noch schwieriger geworden istFür die deutsche Übersetzung bitte nach unten scrollen

For english version please scroll down

Marco Brunazzo è Professore associato di Scienza politica presso l’Università di Trento – Italia. Tra i suoi ultimi libri “La politica dell’Unione europea” (con Vincent della Sala, 2019) e “Italy and the European Union: A Rollercoaster Journey” (con Bruno Mascitelli, 2020)

Il rapporto tra italiani e Unione europea è diventato sempre più critico. Tutti i sondaggi mostrano come nell’arco di poco più di un ventennio gli italiani siano passati da convinti sostenitori dell’integrazione comunitaria a euroscettici (Brunazzo e Della Sala 2011). Secondo i dati dell’inchiesta Parlameter 2018, in caso di referendum sull’appartenenza dell’Italia all’UE, solamente il 44% degli elettori esprimerebbe un sicuro voto a favore della permanenza, il peggiore dato tra tutti i paesi membri (Parlameter 2018, 28). Il fatto che il 32% dei rispondenti (anche in questo caso la percentuale maggiore di tutti gli stati membri) esprima un orientamento incerto o preferisca non rispondere indica ancora più chiaramente il senso di smarrimento degli italiani.

Anche tra i partiti politici il sostegno all’Unione europea ha cessato di essere un tema condiviso tra tutte le principali forze politiche. Non è un caso che alle elezioni politiche del 2018 il partito populista Movimento 5 Stelle (che tra il 2014 e il 2019 aderiva al gruppo politico del Parlamento europeo Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy di Nigel Farage) abbia ottenuto il 33% dei voti. Nelle elezioni europee del 2019, inoltre, la Lega di Matteo Salvini (dichiaratamente favorevole a una uscita dell’Italia dall’Unione economica e monetaria, se non dall’UE tout court) ha ottenuto il 34% dei consensi, raggiungendo un successo di portata storica per questo partito.

La crisi del coronavirus non ha cambiato questo trend. Anzi, per certi aspetti, l’ha accelerato. Una ricerca realizzata dall’Istituto Affari Internazionali, dalla Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo e dal Laboratorio Analisi Politiche e Sociali (Laps) dell’Università di Siena pubblicata nel maggio 2020 lo mostra chiaramente (Istituto affari Internazionali 2020). E’ da notare che la raccolta dei dati è stata fatta dopo l’importante Consiglio europeo del 23 aprile, e quindi dopo l’approvazione dell’accordo sul Meccanismo europeo di stabilità che potrebbe portare all’Italia 35 o 36 miliardi di euro per misure relative al settore sanitario.

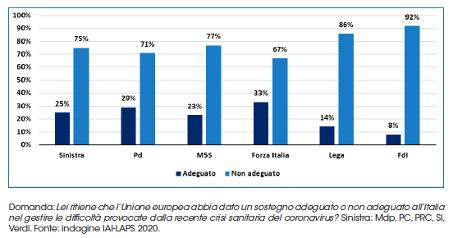

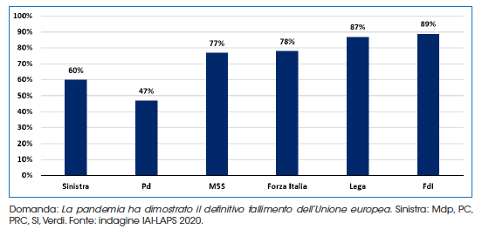

Per quanto riguarda l’Unione europea, ben il 79% degli intervistati ritiene che gli sforzi dell’UE a sostegno dell’Italia per fronteggiare la crisi siano stati poco o per nulla adeguati, e il 73% ritiene che la pandemia abbia dimostrato il completo fallimento dell’UE. Dato ancora più interessante, le critiche all’UE accomunano gli elettori di tutti i partiti (figg. 1 e 2).

In effetti, stupisce che l’euroscetticismo abbia finito per dilagare anche tra gli elettori del Partito democratico, tradizionalmente il partito più europeista della cosiddetta Seconda Repubblica. D’altro canto, il 71% dell’opinione pubblica ritiene che l’Italia sia stata lasciata da sola di fronte all’emergenza sanitaria. Tuttavia, in questo caso, il 47% degli elettori di centrosinistra ritiene che l’Italia sia stata trattata ingiustamente contro l’87% degli elettori della Lega e di Fratelli d’Italia.

Da segnalare, infine, che, rispetto a un anno fa, la percentuale di coloro che ritiene che vada mantenuta la libera circolazione delle persone nell’UE sia diminuita di ben 10 punti percentuali (61% nel 2020).

Ciò detto, non c’è grande voglia di sovranismo in Italia. Anzi, gli italiani sono convinti che una crisi di portata globale come quella del coronavirus possa essere superata solamente con una maggiore cooperazione internazionale, come ritiene il 68% degli intervistati. Solamente il 32% di loro ritiene che una così importante crisi abbia dimostrato la necessità di una maggiore indipendenza dagli altri stati.

Da questa consapevolezza della necessità di collaborazione occorre ripartire se si vuole che gli italiani si riconciliano con l’UE. Proposte come quella formulata il 18 maggio 2020 dalla Cancelliera tedesca Angela Merkel e del Presidente francese Emmanuel Macron di creare un fondo per facilitare la ripresa europea vanno nella giusta direzione, perché mostrano che un’Europa solidale esiste. Aiutano a rovesciare una narrazione che ha trovato ampia eco nei media italiani secondo cui gli aiuti per contrastare la diffusione del virus sono venuti più dalla Cina e dagli Stati Uniti che dai paesi dell’UE. Si tratta di una narrazione evidentemente falsa, ma che ha trovato sponde anche all’interno del Governo italiano di Giuseppe Conte.

Se L’UE vuole riconquistare il cuore e le menti dei cittadini deve dimostrare di essere in grado di rispondere alle loro necessità più pressanti. Ma questo non deve esimere i paesi economicamente in difficoltà, come l’Italia, ad affrontare i nodi che minano la sua capacità di crescita. L’assunzione di responsabilità verso l’UE dimostrata da Merkel e Macron non può non essere accompagnata da un supplemento di responsabilità del governo italiano a utilizzare i fondi europei per iniziative che permettano al Paese di affrontare i suoi problemi strutturali. Solo adottando decisioni ambiziose sia a livello nazionale che europeo si può sconfiggere il populismo che ha avuto grande fortuna in Italia, un paese definito, non senza ragione, “il paradiso populista” (Hermet 2001). Un populismo che si è nutrito da una parte della narrazione che l’Europa sia largamente incerta di fronte alle sfide più importanti e, dall’altra, della frustrazione prodotta da un’Italia che fatica a ritrovare una sua posizione in uno scacchiere internazionale assai più complesso di un tempo.

Riferimenti bibliografici

Brunazzo, M. e V. Della Sala, From Salvation to Pragmatic Indifference? Europe in Italian Political Discourse, in R. Harmsen, J. Schild (a cura di), Debating Europe: The 2009 European Parliament Elections and Beyond, Baden-Baden: Nomos, p. 69-84.

Hermet, G. (2001), Les populismes dans le monde. Une historie sociologique, XIX-XX siècle, Fayard, Parigi, 2001.

Istituto Affari Internazionali (2020), Emergenza coronavirus e politica estera. L’opinione degli italiani sul governo, l’Europa e la cooperazione internazionale. Rapporto di ricerca a cura di DISPOC/LAPS (Università di Siena) e IAI, disponibile all’URL https://www.affarinternazionali.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LAPS-IAI_2020_covid.pdf (ultimo accesso 20 maggio 2020).

Parlamento europeo (2018), Parlameter 2018. Taking up the challenge: From (silent) support to actual vote, disponibile all’URL https://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/files/be-heard/eurobarometer/2018/parlemeter-2018/report/en-parlemeter-2018.pdf (ultimo accesso 20 maggio 2020).

Questo è un contributo al blog „Insieme o da soli fuori dalla crisi? L’Unione Europea ad un bivio di fronte alle sfide poste dal virus corona“. Per saperne di più sul progetto, clicca qui!

—

Marco Brunazzo ist außerordentlicher Professor für Politikwissenschaft an der Universität Trient – Italien. Zu seinen jüngsten Büchern gehören „La politica dell’Unione europea“ (mit Vincent della Sala, 2019) und „Italy and the European Union: A Rollercoaster Journey “ (mit Bruno Mascitelli, 2020).

Die Beziehung zwischen den Italienern und der Europäischen Union ist in letzter Zeit immer schwieriger geworden. Alle Umfragen zeigen, dass die Italiener innerhalb von etwas mehr als zwanzig Jahren von überzeugten Befürwortern der EU-Integration zu Euroskeptikern geworden sind (Brunazzo und Della Sala, 2011). Nach den Umfragedaten von Parlameter 2018 würden im Falle eines Referendums über die EU-Mitgliedschaft Italiens nur 44% der Wähler ein sicheres Votum für einen Verbleib abgeben, der schlechteste Wert unter allen Mitgliedsländern (Parlameter 2018, 28). Die Tatsache, dass 32% der Befragten (wiederum der höchste Prozentsatz aller Mitgliedsstaaten) Unentschlossenheit zum Ausdruck bringen oder es vorziehen, nicht zu antworten, zeigt noch deutlicher, wie verunsichert die Italiener sind.

Selbst unter den politischen Parteien ist die Unterstützung für die Europäische Union kein einendes Thema mehr für alle wichtigen politischen Kräfte. Es ist kein Zufall, dass bei den Parlamentswahlen 2018 die populistische Partei Movimento 5 Stelle (die sich zwischen 2014 und 2019 der Fraktion Europe of Freedom and Direct Democarcy von Nigel Farage im Europäischen Parlament anschloss) 33% der Stimmen erhielt. Bei den Europawahlen 2019 erhielt die Lega von Matteo Salvini (die sich offen für einen Austritt Italiens aus der Wirtschafts- und Währungsunion, wenn nicht gar für einen Austritt aus der EU aussprach) 34% der Stimmen und erzielte damit einen historischen Erfolg.

Die Coronavirus-Krise hat an diesem Trend nichts geändert. Im Gegenteil, in gewisser Hinsicht hat sie ihn beschleunigt. Dies zeigen Untersuchungen des Istituto Affari Internazionali, der Stiftung Compagnia di San Paolo und des Laboratorio Analisi Politiche e Sociali (Laps) der Universität Siena, die im Mai 2020 veröffentlicht wurden (Istituto Affari Internazionali 2020). Es sei darauf hingewiesen, dass die Datenerhebung nach der wichtigen Tagung des Europäischen Rates vom 23. April und somit nach der Einigung über den Europäischen Stabilitätsmechanismus erfolgte, die Italien 35 oder 36 Milliarden Euro für Maßnahmen im Gesundheitssektor einbringen könnte.

Was die Europäische Union betrifft, so glauben 79% der Befragten, dass die Bemühungen der EU zur Unterstützung Italiens bei der Bewältigung der Krise wenig oder nicht mehr ausreichend waren, und 73% glauben, dass die Pandemie das völlige Versagen der EU gezeigt hat. Interessanter ist, dass die Kritik an der EU von Wählern aller Parteien geteilt wird (Abb. 1 und 2).

Es ist in der Tat erstaunlich, dass sich der Euroskeptizismus schließlich sogar unter den Wählern des Partito Democratico, der traditionell pro-europäischsten Partei in der so genannten Zweiten Republik, verbreitet hat. Andererseits sind zwar 71% der Italiener der Meinung, das Italien während des Corona-Notstandes alleine gelassen wurde. Allerdings sind dabei nur 47% der Mitte-Links-Wähler der Meinung, dass Italien ungerecht behandelt wurde. Unter den Wählern der Lega und der Fratelli d’Italia sind das 87%.

Schließlich ist anzumerken, dass im Vergleich zu vor einem Jahr der Prozentsatz derjenigen, die glauben, dass die Freizügigkeit in der EU beibehalten werden sollte, um bis zu 10 Prozentpunkte zurückgegangen ist (61% im Jahr 2020).

Dennoch gibt es in Italien keinen großen Wunsch nach Souveränismus. Im Gegenteil, die Italiener sind überzeugt, dass eine globale Krise wie die Coronavirus-Krise nur durch eine stärkere internationale Zusammenarbeit überwunden werden kann, wie 68% der Befragten glauben. Nur 32% von ihnen meinen, dass eine so einschneidende Krise die Notwendigkeit einer größeren Unabhängigkeit von anderen Staaten gezeigt hat.

Aus diesem Bewusstsein für die Notwendigkeit der Zusammenarbeit heraus ist es notwendig, neu anzufangen, wenn sich die Italiener mit der EU versöhnen wollen. Vorschläge wie der, den am 18. Mai 2020 Bundeskanzlerin Angela Merkel und der französische Staatspräsident Emmanuel Macron unterbreitet haben und der auf die Schaffung eines Fonds zur Erleichterung des europäischen Aufschwungs abzielt, gehen in die richtige Richtung, denn sie zeigen, dass ein solidarisches Europa existiert. Sie tragen dazu bei, ein Narrativ zu entkräften, das in den italienischen Medien einen breiten Niederschlag gefunden hatte das besagte, dass aus China und den Vereinigten Staaten zur Bekämpfung der Ausbreitung des Virus mehr Hilfe gekommen wäre als aus den EU-Ländern. Dieses Narrativ ist offensichtlich falsch, aber es hat bis in die italienische Regierung von Giuseppe Conte Resonanz gefunden.

Wenn die EU die Herzen und Köpfe ihrer Bürger zurückgewinnen will, muss sie zeigen, dass sie in der Lage ist, auf ihre dringendsten Bedürfnisse einzugehen. Aber dies darf wirtschaftlich angeschlagene Länder wie Italien nicht davon befreien, sich den Problemen zu stellen, die ihre Wachstumsfähigkeit untergraben. Die von Merkel und Macron demonstrierte Bereitschaft gegenüber der EU Verantwortung zu übernehmen, kann nur mit einer zusätzlichen Verantwortung der italienischen Regierung einhergehen, europäische Mittel für Initiativen zu verwenden, die es dem Land ermöglichen, seine strukturellen Probleme anzugehen. Nur wenn wir sowohl auf nationaler als auch auf europäischer Ebene ehrgeizige Entscheidungen treffen, können wir den Populismus besiegen, der in Italien großen Erfolg hatte, einem Land, das nicht ohne Grund als „das Paradies des Populismus“ bezeichnet wird (Hermet 2001). Ein Populismus, der sich einerseits von dem Bild genährt hat, Europa sei angesichts der wichtigsten Herausforderungen weitgehend unentschlossen, und andererseits von der Frustration eines Italiens, das darum kämpft, seine Position auf internationalem Parkett wiederzuerlangen, das viel komplexer geworden ist, als es einst war.

Bibliografie

Brunazzo, M. e V. Della Sala, From Salvation to Pragmatic Indifference? Europe in Italian Political Discourse, in R. Harmsen, J. Schild (a cura di), Debating Europe: The 2009 European Parliament Elections and Beyond, Baden-Baden: Nomos, p. 69-84.

Hermet, G. (2001), Les populismes dans le monde. Une historie sociologique, XIX-XX siècle, Fayard, Parigi, 2001.

Istituto Affari Internazionali (2020), Emergenza coronavirus e politica estera. L’opinione degli italiani sul governo, l’Europa e la cooperazione internazionale. Rapporto di ricerca a cura di DISPOC/LAPS (Università di Siena) e IAI, disponibile all’URL https://www.affarinternazionali.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LAPS-IAI_2020_covid.pdf (letzter Aufruf 20. Mai 2020).

Parlamento europeo (2018), Parlameter 2018. Taking up the challenge: From (silent) support to actual vote, disponibile all’URL https://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/files/be-heard/eurobarometer/2018/parlemeter-2018/report/en-parlemeter-2018.pdf (letzter Aufruf 20. Mai 2020).

Übersetzung Albert Drews unter Verwendung von www.DeepL.com/Translator

Dies ist ein Beitrag im Rahmen des Blog-Projekts „Gemeinsam oder Einsam aus der Krise? Die Europäische Union am Scheideweg angesichts der Herausforderungen durch den Corona-Virus“. Erfahren Sie hier mehr über das Projekt!

—

Italy and the EU: a relationship that the coronavirus has made even more difficult

Marco Brunazzo is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Trento – Italy. His latest books include „La politica dell’Unione europea“ (with Vincent della Sala, 2019) and „Italy and the European Union: A Rollercoaster Journey“ (with Bruno Mascitelli, 2020).

The relationship between Italians and the European Union has become increasingly critical. All the surveys show that in the space of just over twenty years Italians have gone from being convinced supporters of EU integration to Eurosceptics (Brunazzo and Della Sala, 2011). According to the data from the Parlameter 2018 survey, in the event of a referendum on Italy’s membership of the EU, only 44% of voters would vote for permanence, the worst figure among all member states (Parlameter 2018, 28). The fact that 32% of respondents (again the highest percentage of all member states) express an uncertain orientation or prefer not to respond indicates even more clearly the sense of bewilderment of Italians.

Even among political parties, support for the European Union has ceased to be a shared theme among all the main political forces. It is no coincidence that in the 2018 parliamentary elections the populist party Movimento 5 Stelle (which joined Nigel Farage’s Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy political group in the European Parliament between 2014 and 2019) won 33% of the vote. In the 2019 European elections, moreover, Matteo Salvini’s League (which was openly in favour of Italy leaving the Economic and Monetary Union, if not the EU tout court) obtained 34% of the votes, achieving a historic success for this party.

The coronavirus crisis hasn’t changed that trend. In fact, in some ways, it has accelerated it. Research carried out by the Istituto Affari Internazionali, the Compagnia di San Paolo Foundation and the Laboratorio Analisi Politiche e Sociali (Laps) of the University of Siena published in May 2020 clearly shows this (Istituto Affari Internazionali 2020). It should be noted that the data collection was made after the important European Council of 23 April, and therefore after the approval of the agreement on the European Stability Mechanism which could bring Italy 35 or 36 billion euros for measures related to the health sector.

Concerning the European Union, as many as 79% of respondents believe that the EU’s efforts in support of Italy to tackle the crisis have been little or no longer adequate, and 73% believe that the pandemic has demonstrated the EU’s complete failure. More interestingly, the criticism of the EU is shared by voters from all parties (Figs. 1 and 2).

Indeed, it is astonishing that Euroscepticism has ended up spreading even among the voters of the Democratic Party, traditionally the most pro-European party in the so-called Second Republic. On the other hand, 71% of public opinion believes that Italy has been left alone in the face of the health emergency. However, in this case, 47% of centre-left voters believe that Italy has been treated unfairly, compared with 87% of the the Lega and Fratelli d’Italia voters.

Finally, it should be noted that, compared to a year ago, the percentage of those who believe that the free movement of people in the EU should be maintained has decreased by as much as 10 percentage points (61% in 2020).

That said, there is no great desire for sovereignty in Italy. On the contrary, Italians are convinced that a global crisis such as the coronavirus crisis can only be overcome with greater international cooperation, as 68% of respondents believe. Only 32% of them believe that such an important crisis has demonstrated the need for greater independence from other states.

From this awareness of the need for cooperation it is necessary to start again if Italians are to reconcile with the EU. Proposals like the one made on 18 May 2020 by German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron to create a fund to facilitate European recovery head in the right direction, because they show that a Europe of solidarity exists. They help to overturn a narrative that has found wide coverage in the Italian media that aid to combat the spread of the virus has come more from China and the United States than from EU countries. This narration is obviously false, but it has also found its way into the Italian government of Giuseppe Conte.

If the EU wants to regain the hearts and minds of its citizens, it must show that it is able to respond to their most pressing needs. But this must not exempt economically struggling countries, such as Italy, from facing the knots that undermine its capacity for growth. The assumption of responsibility towards the EU demonstrated by Merkel and Macron cannot but be accompanied by an additional responsibility of the Italian government to use European funds for initiatives that allow the country to address its structural problems. Only by taking ambitious decisions at both national and European level, we can defeat the populism that has had great success in Italy, a country defined, not without reason, „the populist paradise“ (Hermet 2001). A populism that has nourished on the one hand the narration that Europe is largely uncertain in the face of the most important challenges and, on the other, the frustration produced by an Italy that is struggling to regain its position in an international chessboard much more complex than it once was.

Bibliographic information

Brunazzo, M. e V. Della Sala, From Salvation to Pragmatic Indifference? Europe in Italian Political Discourse, in R. Harmsen, J. Schild (a cura di), Debating Europe: The 2009 European Parliament Elections and Beyond, Baden-Baden: Nomos, p. 69-84.

Hermet, G. (2001), Les populismes dans le monde. Une historie sociologique, XIX-XX siècle, Fayard, Parigi, 2001.

Istituto Affari Internazionali (2020), Emergenza coronavirus e politica estera. L’opinione degli italiani sul governo, l’Europa e la cooperazione internazionale. Rapporto di ricerca a cura di DISPOC/LAPS (Università di Siena) e IAI, disponibile all’URL https://www.affarinternazionali.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LAPS-IAI_2020_covid.pdf (letzter Aufruf 20. Mai 2020).

Parlamento europeo (2018), Parlameter 2018. Taking up the challenge: From (silent) support to actual vote, disponibile all’URL https://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/files/be-heard/eurobarometer/2018/parlemeter-2018/report/en-parlemeter-2018.pdf (letzter Aufruf 20. Mai 2020).

Übersetzung Clara Dehlinger unter Verwendung von www.DeepL.com/Translato

This is a contribution to the blog project „Together or alone out of the crisis? The European Union at a crossroads in the face of the challenges posed by the corona virus“. Learn more about the project here!

Fig.1. UE e sostegno all’Italia per intenzioni di voto/Abb. 1: Unterstützung Italiens durch die EU, aufgeschlüsselt nach Wahlabsichten. Frage: Sind Sie der Meinung, dass die Europäische Union Italien bei der Bewältigung der Schwierigkeiten, die durch die Corona-Krise hervorgerufen wurden, angemessenen oder nicht angemessenen unterstützt hat? (Adeguato: angemessen, Non adeguato: nicht angemessen). Unter „Sinistra“ werden die Parteien Mdp, PC, PRC, SI und Verdi zusammengefasst.

Fig.2. Pandemia e fallimento dell’UE per intenzioni di voto/Abb. 2: Das Versagen der EU in der Pandemie, aufgeschlüsselt nach Wahlabsichten. Dargestellt ist die Unterstützung der Aussage: Die Pandemie hat das definitive Versagen der Europäischen Union gezeigt. Unter „Sinistra“ werden die Parteien Mdp, PC, PRC, SI und Verdi zusammengefasst.